POPL Lecture notes: The essence of Javascript

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Object Literals

- 3. The empty object

- 4. Top level bindings and the top level object

- 5.

this.this: An inconsistency in Javascript semantics - 6. Functions

- 7. Functions evaluate to closures

- 8. Functions as methods

- 9. Methods to populate objects

- 10. Careful when invoking methods in an unguarded context

- 11. Functions are objects

- 12. Functions as object constructors

- 13. The

Objectconstructor - 14. Prototype Inheritance in Javascript

- 15. The special constructors

ObjectandFunction - 16. The Ontology of Javascript

- 17. Constructors and prototypes in Javascript

- 17.1. Every object has a constructor

- 17.2.

constructorproperty not owned by all objects - 17.3. Prototypes own

constructorproperty - 17.4. Objects created via

newdo not own aconstructororprototypeproperty - 17.5. An object inherits from its parent, i.e., its constructor's prototype.

- 17.6. Mutating constructor's prototype affects inheritance protocol of future progeny, not past.

- 18. Inheriting directly from an object

- 19. A final bit of confusion with constructors

- 20. Source code

1 Introduction

The goal of this lesson is to gain an understanding of the key concepts in Javascript, a modern object-oriented language. Javascript's object regime is simple, but somewhat confusing. Our goal is not to develop an encyclopaedic knowledge of Javascript, but to understand how Javascript works by modeling its object construction and interaction behaviour in Scheme.

2 Object Literals

An object can be created literally

a = {x: 3, y: 4};

The fields x and y are accessed as

a.x // => 3 a['x'] // =>3

Not that the access a['x'] emphasizes that the symbol x is looked

up in the object a.

3 The empty object

The empty object is {}, which contains no fields.

console.log({} === {}) // => false

Notice that a and b are both empty, but distinct structures.

4 Top level bindings and the top level object

Javascript, when run in an interactive read-eval-print mode, consists of a top-level. A top level binding can be made as follows:

var b = 5;

Every top level binding is a field assignment in a predefined global

object. The global object may be accessed through the top-level

identifier this. Therefore, at the top-level, the following are all

equivalent:

var b = 5; b = 5; this.b = 5;

You may want to try typing this at the top level to find out what it

looks like.

5 this.this: An inconsistency in Javascript semantics

We have just learned that a top-level binding is in fact a field in

the object accessed via the top level variable this. Therefore it

makes perfect sense for the expression this.this to evaluate to the

top level object itself. That is, this.this should be identical to

this. The current implementations of Javsacript (I have checked

node.js and Firefox) instead return undefined. This can only be

described as a flaw in Javascript's design.

this.this // => undefined

6 Functions

A function consists of a set of parameters and a body:

var add = function(x,y) {

return x+y;

};

c = add(3, 4); // invoking add with arguments 3,4

console.log(c);

7 Functions evaluate to closures

Functions in javascript evaluate to closures. This makes it possible to write functional programs in Javsacript.

var addStaged = function(x) {

return function(y) {

return x+y;

};

};

var add3 = addStaged(3); add3(5); // => 8

8 Functions as methods

Functions may also be installed as methods in an object. In this

role, they operate on the fields of the object. A function body may

contain a reference to the free identifier this. Notice that the

token this is not a keyword; it is an identifier. It is not

explicitly declared. Instead, one should assume that this is

implicitly declared as the first parameter of the function. A

function f when invoked in the context of an object a, such as

a.f(...) behaves as a method and this in the body of f, if it

exists as a free variable, refers to the object a.

var a = {x : 5};

a.incr = function() {

this.x = this.x + 1;

}

a.incr(); // in this call, this in the body of the function is bound to a.

a.x // => 6

9 Methods to populate objects

Functions as methods can be used to populate objects. Consider the

function Point defined below:

var Point = function(x,y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

};

var a = {};

a.Point = Point;

a.Point(2,3); // populates a's x and y fields

a.x; // => 2

a.y; // => 3

a; // {Point: [Function], x: 2, y: 3}

10 Careful when invoking methods in an unguarded context

Notice that the function Point contains the identifier this in

its body. Presumably, Point should be invoked in the context of an

object. What would happen if, instead we invoked Point in an

unguarded way, as below?

var p2 = Point(2,3) // invoking Point

The answer to this obviously depends on what is the binding of this.

It turns out that this has a top-level binding to an object.

Exactly what this object is, depends on the implementation. Thus,

Point(2,3) is to be interpreted as this.Point(2,3), where this

is top-level bound. Then, this.x and this.y refer to fields of

the top level object.

p2 // => void this.x // => 2 x is a field in the top level object =this= x // => 2 x is a top level field and is identical to =this.x=

11 Functions are objects

In Javascript, every function is an object. Some fields come automatically with every function definition.

add // => [Function]

11.1 apply

The field apply of a function object is itself a function that

takes two arguments, an object and an array of arguments. We could

use apply to explicitly populate objects.

add.apply(null, [1, 2]) // => 3

var a = {};

Point.apply(a, [2, 3]);

a.x; // 2

a.y; // 3

In the add.apply example, the first argument is the null value.

Since add's body doesn't have a free occurrence of this, it

doesn't matter what is passed as the first argument to add.apply.

In the Point.apply example, the first argument passed is the freshly

created object a. As a result of this invocation and the execution

of the body of Point, a gets populated with fields x and y.

11.2 Prototype

Another field that every function object comes equipped with is

prototype. The significance of this field will be explained later,

when we study Javascript's inheritance structure. The prototype

field in Javascript is mutable.

11.3 Other fields

Since a function is an object, there is nothing preventing anyone from

adding any number of fields or modifying any field, including apply.

(Try it, don't expect apply to work as a function after that!)

Point.apply = 5;

12 Functions as object constructors

Objects in Javascript are formally constructed using functions. In

this role, functions are called constructors. The keyword new

indicates that the function is playing the role of a constructor.

var p1 = new Point(2,3); p1.x; // => 2 p1.y; // => 3

The expression new Point(2,3) creates an empty object, then runs the

function Point(2,3) in the context of that new object, and finally

returns the new object. Note that without new, Point(2,3) would

simply populate the top-level object this instead of creating a new

object.

In Javascript, by convention, constructors are capitalized (so,

Point, instead of point).

12.1 The constructor field

Objects are created from constructors. The constructor field

of an object at that object's creation time points to the

function object that created that object. The constructor

field is mutable.

p1.constructor === Point; // => true

13 The Object constructor

new Object() constructs an empty object and is

equivalent to {}.

a = new Object();

14 Prototype Inheritance in Javascript

The field prototype if it exists and is an object, has a special

role. Inheritance happens through this field.

Every function already has a prototype field. Consider the function

Point defined earlier. Suppose we populate its (already existing)

prototype with the field z.

Point.prototype // => {}

Point.prototype.z = 4; // create a field z in the prototype object.

p3 = new Point(1,2);

p3.z // => 4

p3.constructor === Point // => true

p3.constructor.prototype.z // => 4

The field z is inherited by p3 via its constructor Point's

prototype object. In other words, when the field z is looked up in

the object p3 and it is not found, then look up proceeds by looking

into the constructor's prototype that existed when p3 was created.

15 The special constructors Object and Function

Javascript initial environment comes with two predefined function

objects: Object and Function.

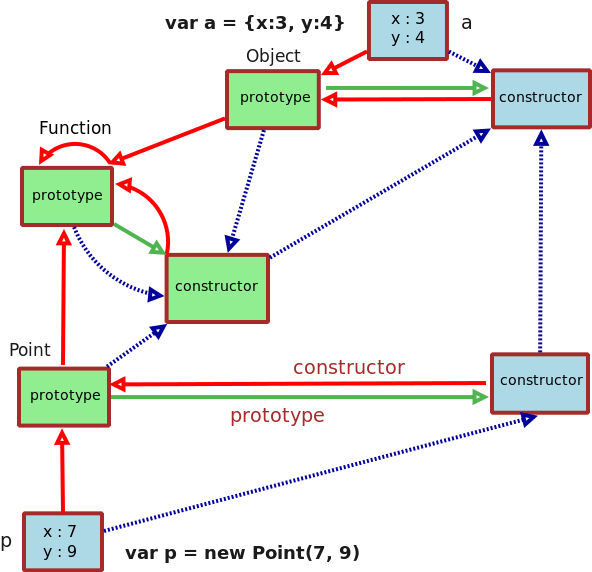

16 The Ontology of Javascript

Notes

- The diagram shows the state of the Javascript runtime after the

creation of the primordial objects, one user defined function

object

Pointand two user defined objectspandaand nothing else.

- Boxes are objects.

- Green boxes are function objects. Blue boxes are regular objects.

- A Red arrow from an object points to the object's

constructorfield. - A Green arrow from an object points the object's

prototypefield. - A Blue arrow indicates the object's parent. Every object has a

parent, except the prototype of

Object. Unlike the Red and Blue arrows, which denote mutable fields, the Blue arrow does not denote a field and can not be mutated. - A binding inside a box refers to the binding owned by that box's object.

17 Constructors and prototypes in Javascript

17.1 Every object has a constructor

In Javascript, every object has a constructor. The constructor is a

function object. Unless mutated, the object's constructor field

points to the object's constructor.

var G = function() {};

var g = new G();

g.constructor === G // true

G.constructor === Function // true

Function.constructor === Function // true

Object.constructor === Function // true

In the example above, the constructor of g is G. Function is

the constructor of the objects G, Function and Object.

17.2 constructor property not owned by all objects

Some objects come predefined with the constructor property. Not all

do.

g.hasOwnProperty("constructor") // false

G.hasOwnProperty("constructor") // false

Here, neither g nor G own the constructor field.

17.3 Prototypes own constructor property

Unless explicitly set, only the prototype of a function owns a

constructor field.

G.prototype.constructor === G; // => true

G.prototype.hasOwnProperty("constructor") // true

17.4 Objects created via new do not own a constructor or prototype property

An object created via new does not own a constructor or

prototype property unless these are explicitly set by the object.

var G = function() {};

var g = new G();

g.constructor === G; // true

g.hasOwnProperty("constructor") === false // true

g.prototype === undefined // true

The prototype property of g does not exist unless it is set by

g or one of its ancestors.

17.5 An object inherits from its parent, i.e., its constructor's prototype.

The object inherits from its parent object. The parent is equal to

the value of the prototype field of the object's constructor at the

time of creation of the object. The object's inheritance protocol is

hardwired: it does not change if any field is mutated.

var G = function() {};

var g = new G();

G.prototype.x = 5;

g.x === 5 // true

17.6 Mutating constructor's prototype affects inheritance protocol of future progeny, not past.

If a constructor's prototype field is mutated, that does not affect

the inheritance protocol of objects previously created by that

constructor; it affects only the objects created after the mutation.

var G = function() {};

var g = new G();

var s = new Object();

G.prototype = s;

s.z = 7;

g.z // undefined

var h = new G();

h.z === 7; // true

18 Inheriting directly from an object

Given a regular object a, we want to create an object b that

inherits its fields. Douglas Crockford in his book "Javascript: the

Good Parts" (O'Reilly publications 2008) suggests the function

Object.beget for this purpose:

Object.beget = function(o) {

var F = function() {};

F.prototype = o; // any object constructed by F

// henceforth will inherit from o.

var b = new F();

return b;

};

a = {x:1, y:2};

b = Object.beget(a);

b.x === 1 ; // true

a.z = 5;

b.z === 5; // true

Now, one can see that b inherits a's fields.

19 A final bit of confusion with constructors

Consider the constructors of the object a and the object b that it

begets.

a.constructor === Object ; // true b.constructor === Object; // true

We expect b's constructor field to reflect the function F that

constructed b, but it doesn't.

How can this be explained? Recall that the constructor field is not

owned by b. Instead, it is inherited from a, the prototype of

F, which in turn is b's actual constructor.

This final bit of confusion should be fixed so that b's

constructor is indeed reflected as F.

Object.beget = function(o) {

var F = function() {};

F.prototype = o; // any object constructed by F

// henceforth will inherit from o.

var b = new F();

b.constructor = F;

return b;

};

a = {x:1, y:2};

b = Object.beget(a);

b.x === 1 ; // true

a.z = 5;

b.z === 5; // true

a.constructor === Object; // true

b.constructor !== Object; // true

20 Source code

- ./intro.js

- Experiments to reveal Javascript's object regime